The 1953 MSW grad who changed Louisiana social work history

Seventy years ago, New Orleans looked much the same. Cars lined thin cobblestone streets; music spilled into every corner of the city; streetcars brushed past tourists on wrought-iron balconies.

“I remember enjoying the big, beautiful oak trees, listening to jazz at nice bars on Bourbon Street, eating beignets for the first time at Café Du Monde. I recall taking Mississippi River tours to look at the skyline,” said 103-year-old Elvera Sue Oppliger, who would go on to organize in the Civil Rights movement, make waves in the Louisiana feminist movement, and lead the process of transitioning Shreveport and Bossier City psychiatric patients from asylums to community centers. “The skyline has changed some, but not too much. Even the apartments I lived in in the French Quarter are still there.” Oppliger graduated with a Master of Social Work degree from Tulane University in 1953.

“In many ways, New Orleans is still the same, and that’s what makes it unique. A lot of the places I went to while in school are still there – Pat O’Brien’s, Galatoire’s, even my old hat maker,” said Oppliger. Then, she echoed what many transplants today still say after their first year in the city: “There were a lot of things that I had never experienced before – Mardi Gras, po’boys, raw oysters. That’s part of the charm of New Orleans.”

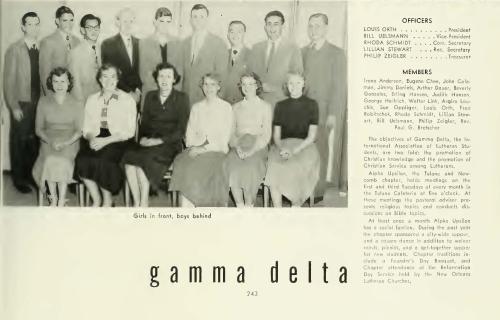

Oppliger was a member of Tulane's chapter of Gamma Delta in 1952. From Jambalaya, Tulane's yearbook.

New Orleans: The city that stands still in time. Yet Oppliger is no stranger to change. An avid activist and changemaker, she made waves in Louisiana politics on multiple fronts. She was a social worker, a civil rights activist, a feminist, and a staunch believer in community.

After graduating with her MSW, Oppliger worked at the New Orleans Mental Health Center for seven years before being recruited by the Louisiana Division of Mental Health to open a Child Guidance Center in Shreveport, where she would go on to change the future of mental healthcare in Louisiana.

A page of the New Orleans States-Item, which later merged with the Times-Picayune, published June 2, 1953, names Oppliger (listed Elvira Dorothy Oppliger) as a Master of Social Work graduate.

The Civil Rights Movement

Louisiana was at the forefront of the country’s civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s. In 1953 – the year Ms. Oppliger graduated – Baton Rouge saw the nation’s first bus boycott. At that same time, Oppliger recalls being glared at for sitting in the back of buses and streetcars with her Black neighbors. But her introduction to the civil rights movement did not really begin until she moved to Shreveport in 1960.

“I met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., once, in a dark room in a Baptist church in Shreveport,” Oppliger shared. “We were afraid of the police, so we met in secret. Dr. King was trying to organize some sit-ins. We did everything quietly so we wouldn’t be noticed. It was a very stressful time in the city.”

Oppliger recalled witnessing voting officials require Black citizens to answer increasingly difficult questions until they were able to legally disqualify them from voting. At the time, Dr. King and local civil rights champion Dr. Cuthbert Ormond “C.O.” Simpkins I worked tirelessly to improve voting access. Dr. Simpkins was harassed by Ku Klux Klan members, law enforcement, and government officials – his home and office were both bombed – until he eventually moved to New York. (He later returned to Shreveport and went on to represent District 4 of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1992–1996.)

“Several people I knew moved away from Shreveport because of how much harassment Black people were experiencing,” said Oppliger. “They were fearful for their lives. Some of them didn’t come back.”

In September of 1963, four Black children were killed by a Ku Klux Klan bombing in Birmingham, Alabama. 450 miles away, civil rights leaders held a protest for those deaths in front of Little Union Baptist Church – a church that still stands in Shreveport today. Police stormed the church on horses, using cattle prongs to brutally dismiss the crowd.

“A police officer [...] pulled me out of the church; then every officer who could get near me beat me. I was left seemingly lifeless on the ground,” wrote Reverand Harry Blake, then the president of the Shreveport chapter of the NAACP, in his book, "Plantations, Protests, Pulpits, Lessons from the Phases of My Life."

The next day, students from Booker T. Washington High School attempted to march to the church in protest of the state-sanctioned violence and were met with police batons, teargas, and 18 arrests.

In 2023, students marched from Booker T. Washington High School to Little Union Baptist Church in honor of the 60th anniversary of that same protest. They were able to complete their demonstration.

“There has been a lot of progress, but it has happened in small steps,” said Oppliger. “Today’s students were respected and allowed to march, and I’m grateful for that. Things are better, but they aren’t perfect.”

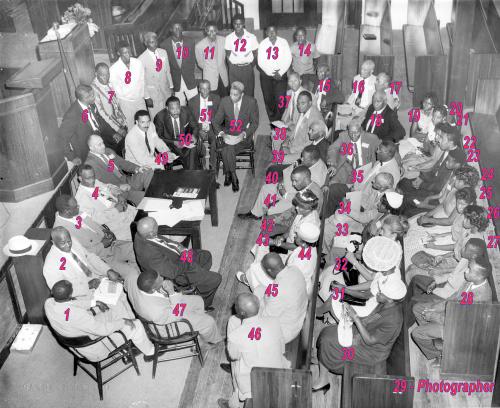

A photo of a Civil Rights meeting at the original Galilee Baptist Church in Shreveport, LA, in mid-August of 1958, shows Dr. C.O. Simpkins (#49) sitting beside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (#50). North Louisiana Civil Rights Coalition is still looking to identify many of the heroes in this photo.

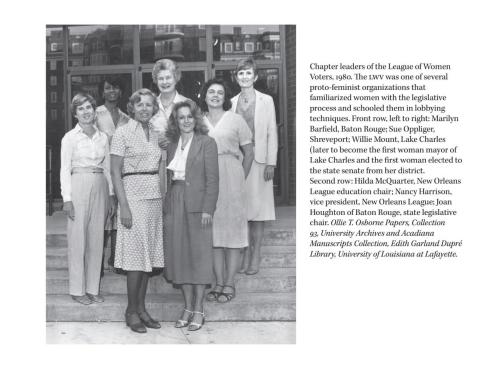

"Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women's Rights Movement in Louisiana, 1950–1997" shows Oppliger as a chapter leader of the League of Women Voters in 1980.

Second-Wave Feminism

The 1960s, 70s, and 80s were also an important time for women’s rights. The second-wave feminist movement in Louisiana called for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, which would guarantee equal protection of women under the law. Though the amendment was ultimately dismissed, women in Louisiana made strides to give wives joint property ownership and decision-making ability, establish women’s shelters, and reform rape laws.

“I was active in Shreveport’s National Organization of Women (NOW) and attended a national conference at which Rosalynn Carter spoke. She was a great supporter of mental health. She was my role model; I respected her very much.”

Oppliger was active in more than just the NOW. She was a board member for Zonta International, the Volunteer Services Bureau, Crisis Intervention Center, Association of Retarded Citizens, Louisiana Association for Mental Health, and the Highland Restoration Association, to name a few.

Oppliger was chairperson for Zonta International’s Z Clubs – service clubs within high schools – for more than a decade. As such, she hosted workshops, helped with the Salvation Army’s Angel Tree Project, and empowered women through Dress for Success. When asked what she was most proud of, she said simply, “Working with the teenage girls.”

“Women didn’t have a lot of opportunities for advancement back then, but I always seemed to be able to get involved with new programs. I had a lot of friends,” said Oppliger, who again stressed the importance of community as a form of empowerment. In 1953, when she graduated, two-thirds of the Master’s and doctoral students were men. Only 45 women received graduate-level degrees that year – and a whopping 80% of them were enrolled in the School of Social Work.

Oppliger remarked on the incredible role models and peers she had in the program. One professor, Edith Schulhofer, made a particular impact. Schulhofer lost her law professorship at the University of Munich because she was Jewish. After fleeing to France and then to New York, she earned an MSW from Columbia and began teaching at Tulane in 1950, where she inspired generations of women to do work that matters. The School of Social Work was also the first school within Tulane to have a female dean - Elizabeth Wisner, who served as Dean from 1939 to 1958.

“I’m proud to have been a leader in the National Association of Social Workers and the League of Woman Voters. I’m glad I was a part of those movements, even though there’s still a lot that we don’t have the answers for,” said Oppliger.

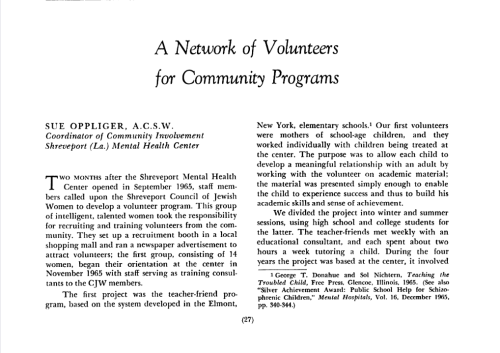

Oppliger published "A Network of Volunteers for Community Programs" in Psychiatric Services in 1971.

Deinstitutionalization in Louisiana

In addition to the turmoil of state violence, sexism, and white supremacy, Oppliger’s life was changing professionally. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy signed the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act. The law decreed that mental institutions – then called insane asylums – were to be replaced by community mental health centers, which would allow patients to live and receive care in their communities.

Oppliger was to lead this transition in North Louisiana. She was one of the first three people employed at Shreveport’s brand-new mental health center in 1965. As the Director of Community Services for Shreveport Mental Health Center, Oppliger established community infrastructure to rehabilitate and socialize schizophrenic children who had previously been held in state institutions.

“We built support systems, set up social clubs in women’s groups and churches, and they met every week to help patients reintegrate to society. We also helped high school and college students tutor the children,” said Oppliger.

The programs marked a groundbreaking change in the treatment of mental health in the United States. Oppliger invited members of the Jewish Federation and the Council of Jewish Women to help design an integrated volunteer program to develop academic confidence and social skills. She hopes the programs can act as a precedent for social workers practicing with clients impacted by what she views as the most pressing social issue of 2024 – incarceration without rehabilitation.

“Volunteers can play a vital role in community mental health programs, not only by augmenting available manpower but by focusing on and reinforcing the healthier aspects of the patients’ functioning,” wrote Oppliger in a 1971 article published in Psychiatric Services. “Their interpersonal skills derive not from formal training, but from their innate nurturing qualities of warmth, sensitivity, enthusiasm, and spontaneity. Their involvement in mental health programs also provides a valuable linkage between the professional staff and the various social systems in the community.”

In the first four years of the program’s existence, it impacted some 111 children, later blooming into a parish-wide program hundreds of volunteers and children strong.

“I grew up on a farm in Kansas – I didn’t even really meet any Black people until I got to Louisiana. But I believe in community, even if that community looks different than me. That’s probably why I chose social work as my profession,” shared Oppliger. “The community work made me more accepting and less prejudiced. I hope it did the same for those volunteers.”

A page of the Times-Picayune, published July 20, 1956, reports that Oppliger (listed Sue Oppliger) will represent the Southeastern Louisiana chapter of the National Association of Social Workers at the International Conference of Social Work in Munich, Germany.

Social Work as a Centenarian

Oppliger retired from full-time social work in 1979, though she continued to do consultation work, picked up real estate and antiquing jobs, continued her volunteerism, and traveled to at least 45 countries. (Her travel began with a Tulane-sponsored trip to Munich in 1956 – which she said made her a more accepting, open-minded social worker – and hasn’t stopped since.)

“At 103, I’m still very much a part of and care about what’s going on. I read the newspaper every day and keep up with things that are going on,” Oppliger said. “I’ve stayed active in every way – in my community, in my body, in my mind.”

She remains committed to service, dedicating time to Zonta International, her church, and the many valuable friendships she has fostered during her journey. So, what does she have to say to today’s social workers? One thing: “Keep working. All we can do is continue to work.”

“I’ve enjoyed everything I’ve done, and I hope I helped people,” Oppliger said. “I hope I made a difference.”

We think we can say with confidence that she did.

Many thanks to Ann Case, University Archivist, for her help with this article.